Since 2012, most of the humans on Earth have been given a nearly annual reminder that there are entire nations of people who are measurably happier than they are. This uplifting yearly notification is known as the World Happiness Report.

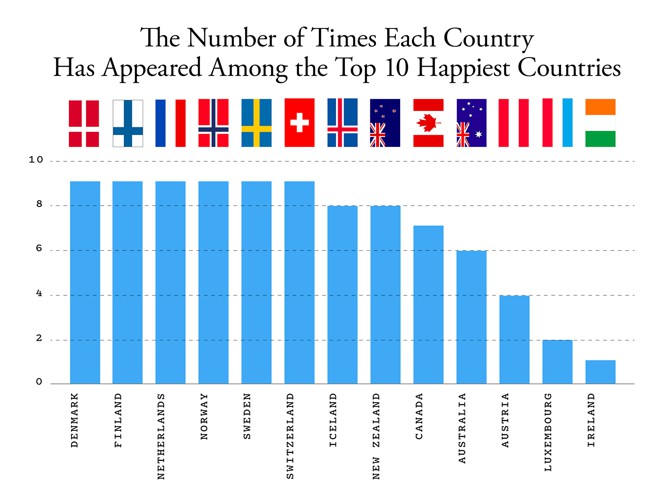

With the release of each report, which is published by the United Nations Sustainable Development Solutions Network, the question is not which country will appear at the top of the rankings, but rather which Northern European country will. Finland has been the world’s happiest country for four years running; Denmark and Norway hold all but one of the other titles (which went to Switzerland in 2015).

The rankings are reliably discouraging for Americans, who have never cracked the global top 10. We are merely in the upper middle class of happiness—respectable, but underwhelming for a country with our level of wealth and self-regard.

Sort of like how the launch of Sputnik in 1957 led Americans to feel like their country was falling behind technologically, or how the results of international standardized tests in the 2000s led them to feel like their kids were falling behind educationally, the happiness rankings have subtly encouraged an anxiety fit for our era of self-optimization: that somewhere, other people are doing things that make them much happier than we are.

This disturbing thought has contributed to the rise of a genre of lifestyle content that aims to help unhappy Americans emulate the daily practices and philosophies of happier places, whether that means taking a dip in frigid water or making your living room super-cozy. Wanting to copy the happiest people in the world is an understandable impulse, but it distracts from a key message of the happiness rankings—that equitable, balanced societies make for happier residents. In the process, a research-heavy, policy-oriented document gets mistaken, through a terrible global game of telephone, for a trove of self-help advice.

Happier isn’t quite the right word for how the Finns compare with the rest of the world—the World Happiness Report is more about contentment than exuberant, smiley happiness. Its rankings are based on each country’s average response to a question that goes something like this: If you imagine a ladder whose rungs are numbered zero to 10, and zero represents your worst possible life and 10 represents your best, which rung would you be on? (Posing this question to at least 1,000 people in 150 or so countries is a resource-intensive undertaking. Gallup, which provides the survey data behind the rankings, declined to tell me the cost of collecting them as part of the Gallup World Poll, but if you’d like, you can buy access to that broader data set for $30,000 a year.)

The UN first took an interest in people’s imaginary life-ladders 10 years ago, after Bhutan’s prime minister at the time, Jigme Thinley, encouraged the organization’s member countries to better incorporate well-being into measurements of social and economic development. His recommendation inspired the first World Happiness Report, released in 2012.

The happiness rankings are a useful countervailing force in a world that tends to take GDP as a proxy for a country’s success, and in the past five years, some governments have launched initiatives dedicated to their citizens’ life satisfaction: The United Kingdom appointed a minister for loneliness, the United Arab Emirates appointed a minister of happiness, and New Zealand reviewed its national budget based on how government spending would affect people’s well-being.

For the people who come up with policies and run countries, the lessons of the report are not shocking: People are more satisfied with their lives when they have a comfortable standard of living, a supportive social network, good health, the latitude to choose their course in life, and a government they trust. The highest echelon of happy countries also tends to have universal health care, ample paid vacation time, and affordable child care.

[Arthur C. Brooks: Find the place you love. Then move there.]

A central takeaway from nine years of happiness reports is that a wealthier country is not always a happier country. In the U.S., “we are living with such incredibly frayed social trust and bad vibes and addictions and so many other things, and still [people say] ‘Don't tax me,’ ‘Don’t tax the rich,’” Jeffrey Sachs, an economist at Columbia University and an editor of the report, told me. “This is part of our politics that I think is all wrong, and that I think is what puts us well behind countries that are not quite as rich as the United States but in my view are much more balanced in their lives.”

Less clear is what an individual person should make of a list of the world’s happiest countries. Sure, it may yield some abstract wisdom about the good life: Sachs views it as a reminder that once you’re comfortable materially, moderation is a healthier attitude than chasing more money and possessions.

[Read: Who actually feels satisfied about money?]

And William Davies, the author of The Happiness Industry: How the Government and Big Business Sold Us Well-Being, observed to me that the list implies “a social understanding of happiness—something that happens between people,” which is a welcome alternative to the default assumption that individual people are responsible for their own misery. He also thinks it can show people which policies to vote for if they want to nudge their society in a happier direction.

The rankings, though, have less to say about what people can do differently in their own lives. Data from the World Happiness Report do indicate that moving to a country higher up in the rankings makes people happier, but personally, I’m not going to uproot myself and move thousands of miles away from most of the people I care about.

This vacuum of actionable information gets filled by media coverage that suggests mimicking aspects of other cultures in hopes that some of their happiness will transfer to you. Most egregious are the articles about various countries’ “secrets” to happiness that readers can implement, such as taking a cold shower in the morning or baking cinnamon buns. Even nuanced reporting can leave the impression that some quirky local custom is essential to people’s fulfillment. Marveling at the warm communal pools in Iceland (No. 4 in the most recent rankings, released in March), writers for The New York Times and the BBC both thought that they could be “key” to the country’s happiness.

One media phenomenon, though, towers above the rest: hygge, a Danish word evoking warmth and coziness that is implied to carry an entire country through harsh Northern European winters and to the top of the happiness rankings. In the mid-2010s, after Denmark had taken the top spot in three out of the first four World Happiness Reports, a spate of hygge-themed books were published, including The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy Living and How to Hygge: The Nordic Secrets to a Happy Life. Hygge has served as marketing copy for sweaters, blankets, and candles, and was once blamed by the Financial Times for helping spike the prices of cozy spices such as cinnamon and cardamom.

Some countries also promote their status when courting tourists. “We do believe that being one of the happiest countries creates curiosity among travelers to come and see themselves what makes us Finns happy,” said Sari Hey, a spokesperson for Visit Finland, and representatives of the tourism boards for Denmark and Norway also told me that they’ve incorporated their happy reputation into their marketing efforts. Visit Finland’s website says that the country’s happiness “has a lot to do with our daily habits: a short walk in the forest, going ice swimming or tasting something fresh from nature.”

Sachs, of the World Happiness Report, doesn’t think that interest in the happiest countries’ customs is entirely misplaced. Denmark and other happy countries embody “a different kind of prosperity, a more equal and shared prosperity, and I think things like hygge are a reflection of that norm,” he told me. “I think it’s something to emulate at an individual level, and something to propound at a political level.”

Taking forest walks and foraging for berries do sound delightful, but a focus on activities and habits reduces entire cultures to individual lifestyle trends and obscures the structural forces that make people satisfied with their lives. No quantity of blankets or candles is going to make up for living in an unequal society with a weak social safety net. The folly of fixating on local customs becomes even clearer if you consider the poverty and violence that are common at the bottom of the rankings: No lifestyle blogger is studying Afghanistan, the least happy country in this year’s report, and recommending that readers avoid Afghan pastimes and customs such as flying kites and going to communal bathhouses.

When I asked Elizabeth Dunn, a psychology professor at the University of British Columbia who studies happiness, how much happier I’d be if I cultivated hygge in my life, she said, “Probably not at all.” She told me that a better way to think about the happiest countries is as putting forward a menu of things that might make some people happier—a list of fresh hypotheses to test in your own life and see what you like. You can’t replicate the structural features that make other countries happier, but experimenting with new habits and activities certainly can’t hurt.

Bear in mind, though, that happiness isn’t found only at the top of the rankings. Sebastian Modak, a freelance travel writer, told me that when he was The New York Times’ 52 Places Traveler in 2019, he met people at every destination who seemed truly happy and had habits that brought them pleasure. “Everywhere had a custom that I could latch on to,” he said. “I hung out with a guy in Siberia who ended every evening with a generous pour of vodka and half a pack of cigarettes. He seemed pretty happy—is that the secret to happiness?”

Perhaps deeper insights can be gained from looking beyond the trends of cozy hearths and nature walks. Even the Nordic countries themselves have a lesser-known cultural ideal that probably brings happiness more reliably than hygge. Jukka Savolainen, a Finnish American sociology professor at Wayne State University, in Michigan, argued in Slate that the essence of his happy home region is best captured by lagom, a Swedish and Norwegian word meaning “just the right amount.”

Savolainen even theorizes that this inclination toward moderation shapes residents’ responses to the happiness ranking’s central question. “The Nordic countries are united in their embrace of curbed aspirations for the best possible life,” he writes. “In these societies, the imaginary 10-step ladder is not so tall.”

Lower expectations: Maybe they’ll make you happier. At the very least, they’ll come in handy for Americans when the 10th World Happiness Report comes out next year.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

from The Atlantic https://ift.tt/3qATB07

via ATLANTIC

No comments:

Post a Comment